Ku Ka'awale

COVID-19 has dramatically changed our lives, and for most of us, not for the better. One thing that this pandemic can’t change, however, seems to be our drive to innovate. While many events were canceled this year, the Hawaii Annual Code Challenge 2020 (https://hacc.hawaii.gov) adapted to an online format. The HACC still hosted a month-long hackathon for students and local developers to develop a software solution to solve the state of Hawaii’s community issues. Various state departments, the University of Hawaii, and local businesses present their challenge prompts to competitors, and each team must build a software solution within a month. Each team’s work would be judged by a panel of judges, and they will chooes the most innovative solution.

Introducing Ku Ka’awale

My team’s submission to the event this year is Ku Ka’awale, a web application that could visualize the wireless data of the University of Hawaii at Manoa campus. With social distancing, the university seeks a solution to visualizing and predicting the campus occupancy. They were able to collect information regarding which wireless access points were used, and how many people are using them. Given this data, we came up with a prototype solution that aims to utilize new technology and present an intuitive user interface.

Devpost: https://devpost.com/software/ku-ka-awale

Source: HACC2020/StayAtHomeCoder

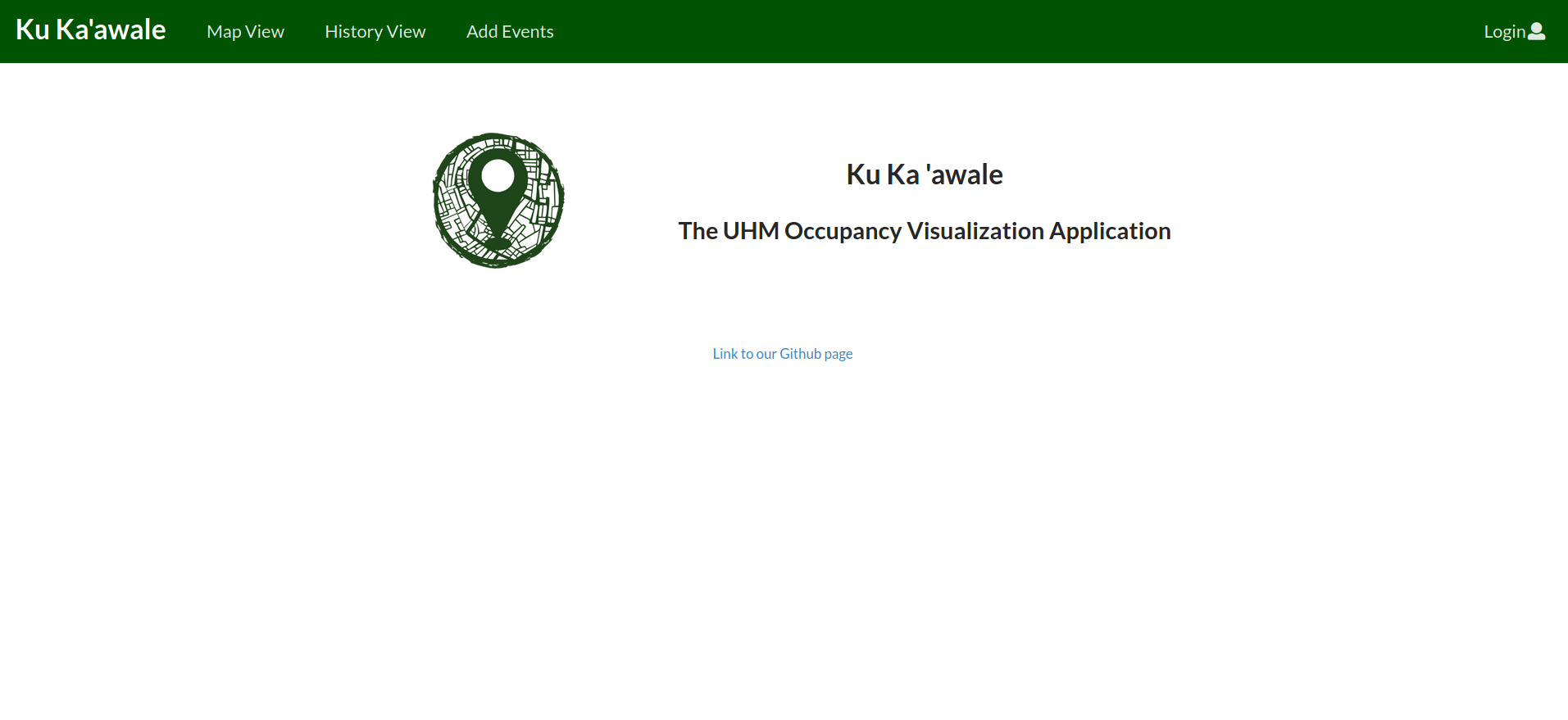

The application was built using the Meteor framework and LeafletJS. There are three pages in this prototype: landing page, map view, history view. Many of the pages are still conceptual mock-ups, and the only page with a functioning map is the map page. The first page shown to the user is the landing page, where basic information is listed.

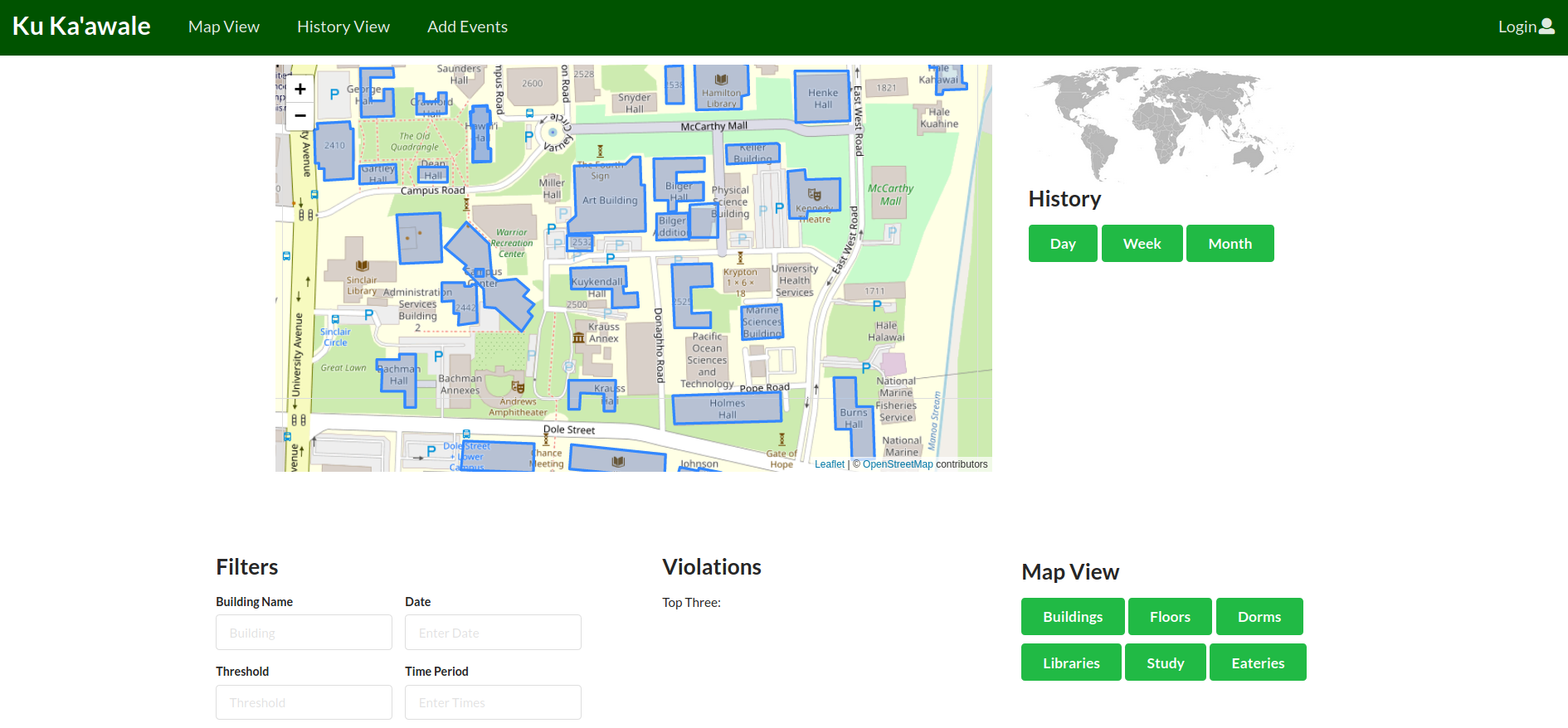

The second page is the map view, where the map of the UH campus is displayed. This functionality uses LeafletJS to display GeoJSON made by our team. There are other concept elements on the page: filters widget, top three occupancy violation widget, and two map filter widgets. These concept elements are only for display, for our team didn’t have the time to implement these features.

The last page in this prototype is the history view. We planned to have a page that shows analytical data about wireless usage. Most of the elements on the page are non-usable, mock-up buttons, and images.

Aspiring team in an unfortunate circumstances

Even with Covid, the competitive spirit still lingers among the competitors. My teammates share the excitement and we were pumped to work on this project. There were many ideas, tools, and concepts being discussed in our chatroom. Many of my teammates were hackathon veterans, so they led the design and implementation of pages. Eric Rivera and Victor Jodar were researching the right technology for this project. With the help of Pauline Wu and Sophia Elize Cruz, we designed the prototype pages and implemented them in Meteor. Lastly, I worked on integrating LeafletJS to React and Meteor.

Even though we were putting a lot of effort into this hackathon, the project was still in the design phase for a long time. We really wanted the application’s design to be innovative and impressive to the judges, to the point that we didn’t have a working prototype until near the end of the competition. We were making choices that seemed to be the right fit at the time, but would later be too time-consuming.

Bad design decisions like wrong tech stack and mapping tools piled up, and we would spend a lot of time fixing them. The ideas were getting too abstract, and the web technology we wanted to use kept changing. When we actually found the right fit for our project, a week flew by and we were behind schedule. The final submission is three pages with only one of them with functionality.

Pick yourself up and keep going

A part of me wants to pick apart this project and try to critically analyze what went wrong. There were many mistakes that we could have fixed by spending even more time on this project. For example, maybe if we chose the current set of tools at the start, then we would’ve gotten a chance at winning the competition. While I certainly could learn a lot from reflecting on what went wrong, I think I learned a lot more by letting go of the mistakes from this project.

It is a difficult time for many of us, and definitely for my teammates. We struggled with balancing college classes, personal time, and this project; during isolation. While this project isn’t the best, we still did the best we can to finish it, and the fact that our project wasn’t competitive helped us understand that fact. When everything is stressful in these hard times, the fact that we create this unremarkable, barely functional application is still better than not making anything at all. What matters is admitting that the project wasn’t great, letting it go, and aiming to do better in the next one.